Christmas Eve of 1945 was a special one for the nation. World War II was finally over, and families would at long last get to celebrate the holidays with loved ones who were coming home from overseas.

The Sodder family wished that their 21-year-old son Joe would have been able to make it home in time for Christmas, but once he was given leave, it was just a matter of time before he would be reunited with his parents and his nine brothers and sisters.

There would be no Christmas tree that year for the Sodder family because they were sad that Joe wouldn’t be with them for the holidays. But they had plans to keep the family traditions of exchanging gifts, attending church, and a special Christmas dinner was in the works.

Christmas was always a special time for George and Jennie Sodder. Celebrating the holidays with family made them grateful for how far they had come in their lives. George Sodder had worked hard all his life to make a name for himself. Now the 50-year-old Italian immigrant was a well respected, successful businessman and owner of his own trucking company.

Giorgio Soddu--George’s given name--immigrated to the United States from Tula, Sardinia, Italy in 1908 when he was just 13-years-old. But in spite of his youth and the prejudices many people felt toward Italian Americans, he worked hard to make a name for himself in his new country.

George lived with relatives in Pennsylvania, attended school, and eventually found work in the railroads carrying water and other supplies to the workers. A few years later he took a job as a truck driver in Smithers, West Virginia, and eventually started his own trucking company. Soon after, he met his wife-to-be, Jennie Cipriani, a storekeeper’s daughter, and the couple moved to Fayetteville, West Virginia where they raised their family of ten beautiful children.

With nine children at home, Christmas Eve of 1945 was a busy time for the Sodder family. That night, 17-year-old Marian, came home from her dime store job with surprise gifts for her three younger sisters, and they wasted no time in opening their early Christmas presents.

By 10 PM, George Sodder had retired to his bedroom on the first floor. His two oldest sons, John, 23, and George Jr., 16, were already asleep in the second floor bedroom that they shared with their two younger brothers who were still playing in the living room.

It was after 10 PM, and Jennie tried to usher the children up to bed, but they asked if they could stay up a little later to continue playing with the toys. Jennie reluctantly agreed, but she reminded Maurice, 14, and Louis, 9, that they still needed to feed the chickens and bring the cows into the barn. They promised their mother that they would, and that they would also put their sisters Martha, 12, Jennie, 8, and Betty, 5, to bed after they finished playing. They also promised to turn out the lights, shut the curtains, and lock the front door.

Jennie headed to bed with three-year-old Sylvia in her arms, leaving the kids playing in the living room next to their older sister Marion who had fallen asleep on the couch. The children played quietly, so as not to waken their sister, and one can imagine that they were talking about the Christmas presents that they would be opening the next morning.

They looked at the mantle clock. ‘It’s getting late’, they probably thought, ‘but we’ll head up to bed in a little while. Just a little more time playing with the toys won’t hurt. After all, it’s Christmas Eve.’

At 12:30 AM, the phone rang and Jennie rushed from the couple’s first floor bedroom to the hallway to answer it. ‘Who would be calling this time of night?’ she thought. She picked up the phone and heard laughter and the clinking of glasses in the background as if a party was going on. A woman asked for a name that Jennie was not familiar with, so she told the woman that she had the wrong number. Jennie later recalled that the woman laughed in a strange way when she told her this, and that she then hung up.

Jennie hung up the phone. She thought that the call was rather odd, but chalked it up to someone at a Christmas Eve party who misdialed the phone. She glanced down the hall and was surprised to see that the lights were still on in the living room, and that the shades had not been drawn. The boys were usually very responsible about locking the house up at night, but Jennie guessed that with all of the excitement about Christmas they had forgotten. With the exception of Marion, all of the kids slept upstairs, so she assumed that they had all gone up to bed.

Careful not to wake Marion who was still asleep on the couch, Jennie closed the curtains, turned off the lights, and checked the front door. It was unlocked. They had also forgotten to lock the door. Those kids. They must be so excited about Christmas. She clicked the lock shut, took one last look around the room, then went back to bed being careful not to wake up her husband, or baby Sylvia who slept in a cradle next to their bed.

At 1 AM, Jennie was awoken by the sound of something hitting the roof of the house with a loud bang followed by a rolling noise. Having already been woken a half-hour earlier by the mysterious phone call, Jennie was tired. She listened for a short time, but didn’t hear any other sounds, and she quickly fell back to sleep. A half-hour later she was awoken by the smell of smoke and got out of bed to investigate. She rushed down the hall and was shocked to find George’s home office engulfed in flames.

Jennie ran back to the bedroom and woke George up, then the couple shouted up the stairs for everyone to get out of the house quickly. Thick, black smoke filled the halls, and flames covered the stairway that led to the children’s bedrooms. John and George Jr. fled the upstairs bedroom they shared with their brothers, singeing their hair on the way out.

During the mayhem, one of the family members tried to call the fire department, but the phone wasn’t working. The line was dead.

The family fled the house and stood on the front lawn in their pajamas, shivering in the freezing cold, watching their house burn down. But something was wrong. The five children who had stayed up late to play with their toys were not with the rest of the family.

“Didn’t you wake your brothers up when you left your bedroom?” George asked John. “I did,” he said, running his hands nervously through his singed hair. “At least, I called out to them and the girls to get up, then Georgie and I ran out of the room. I thought they heard me and that they were right behind us when we ran out. Isn’t that right Georgie?”

George Jr. tried to think back, but the past few minutes were a nightmare. “I don’t know,” he said. “I just don’t know. Everything happened so fast, and there was so much smoke. We were both coughing and yelling for everyone to get up. The smoke was so thick I couldn’t see a thing. If the light wasn’t on downstairs we never would have been able to see where to go.”

The family ran around the yard frantically calling for the kids, but they were nowhere to be found. Then they looked back at the house. The entire bottom floor was now engulfed in flames and an icy cold wind fanned the flames. The kids must be trapped in the upstairs bedrooms.

George and the boys raced back to the house. They tried to go in through the front door, but the flames had spread so quickly that they blocked the way. All George could think of were his five children trapped in the house with no way out.

George and his sons searched for a way back into the house, but it seemed hopeless. At one point, George climbed a wall and broke a side window with his fist, badly cutting his arm. But it was no use. The fire was raging inside the house, and the flames leapt out at him. The only way left to save the children was to attempt to rescue them through an upper window.

George raced around to the side of the house where the ladder always stood, but when he turned the corner he was shocked to find that it was gone. He was beginning to panic, but he had to find a way to save his children. He hit upon the idea to move one of his trucks up to the side of the house, and to climb on top of it to reach the second floor window. Luckily, he always kept the keys in the trucks, so he still had a chance to rescue the kids.

Ignoring the freezing cold, George and his sons ran barefoot across the frozen yard to the trucks. George got behind the wheel of one of them and turned the key in the ignition, but nothing happened. He tried again. Nothing. The engine was dead. ‘How could this be?’ he thought. ‘It started just fine yesterday.’ Leaping from the truck, he ran over to the second truck where John was behind the wheel frantically trying to start it, but that truck was also dead.

George and the boys tore back to the house and looked up at the upper floor. Smoke was beginning to seep out around the corners of the upper windows. They ran to a rain barrel that was next to the house hoping to douse the flames with water, but it was frozen solid. Back on the front lawn, the family stood huddled together in the icy wind, calling out the children’s names, hoping against hope that the kids would hear them and be able to jump out of one of the upstairs windows.

While George and the boys were busy trying to start the trucks, daughter Marion sprinted to a neighbor’s house. She told them about the fire, and asked that they call the Fayetteville Fire Department. The neighbor picked up the phone, but she was unable to reach an operator.

A driver on a nearby road saw the flames and tried calling the fire department from a nearby tavern, but he too was unable to reach an operator. It was Christmas eve, and the local switchboard must have been understaffed.

Exasperated, the neighbor drove into town and finally located fire chief F.J. Morris. In those days, Fayetteville didn’t have a siren to call firefighters to action. Instead, they used a “phone tree” system whereby one firefighter phoned another, who in turn phoned another. But even though the fire chief knew that five children were trapped in the house, he didn’t jump in his car and head over to the Sodder’s to see how he could help or call anyone to make sure the family was safe. He just started the phone chain and waited for the men to arrive.

Back at the Sodder home the family stood huddled together on the lawn on that frigid Christmas morning wearing just their pajamas. They watched helplessly as their home burned to the ground with the five little children trapped inside. Less than an hour after the fire started, the roof collapsed, the house was reduced to a smoldering pile of ashes and burnt timbers, and the five youngest children were surely dead.

Even though the fire department was only two and a half miles away, the fire crew didn’t arrive at the Sodder home until 8 AM, over six hours after the fire started. Later, fire chief Morris would tell the state police that he didn’t know how to drive the fire truck, so he had to wait at the firehouse until the firemen arrived. In addition, since it was Christmas eve, many of the firefighters were away so they were sorely understaffed that night. By the time the fire crew arrived, the only thing they could do was hose down the remains of the house to cool down the ashes. There was basically nothing left of the house itself.

A short time later, local and state police showed up on the scene. They interviewed the family members, sifted through the ashes, and conducted a cursory investigation. By now the house was just a pile of wet cinders, and nothing remained but some burnt timbers, the remains of some home appliances, bits of the tin roof, and the smoldering basement.

By 10 AM fire chief Morris had some news for the family, but it wasn’t what they expected to hear. The firemen had sifted through the ashes, but they hadn’t found any bones, as might have been expected if the children had died in the fire. “But the children had undoubtedly perished in the blaze,” Morris said. “The fire had burned so hot that it must have completely cremated their remains.”

George and Jennie looked at the fire chief dumbfounded. “No trace of the children?” they asked. “The fire burned for less than an hour, and there were five kids. Surely there must be at least some bones left after the fire.” But Morris wouldn’t discuss it further. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but I’ve seen cases like this before. I know it’s hard, but you’re just going to have to accept that the fire cremated their remains.”

Morticians arrived on the scene and the Sodders were told that because no traces of the children’s bodies had been found, the easiest and most respectful way to hold the funerals would be for the parents to pick up a handful of ashes for each of the five children, place the ashes in a box, and bury the ashes in place of the bodies. But George refused this suggestion. He was simply too grief stricken to make such a decision so soon after the tragedy.

Morris told George Sodder to leave the site undisturbed so that the state fire marshal’s office could conduct a more thorough investigation at a later date; but after four days, George and Jennie decided that they could not bear the sight of the charred ground that was once their home. George bulldozed five feet of dirt over the site, filling in what remained of the basement with the intention of turning the space into a memorial garden for his dead children.

The day after the fire, the local Justice of the Peace, who also served as acting coroner, and six local citizens met in the Fayetteville town town hall to hold an inquest into the fire. They came to the quick conclusion that the fire was caused by faulty wiring, and that there was no sign of arson. They ignored Jennie Sodder’s report of hearing something hitting the roof a half hour before the fire started.

The five children had undoubtedly perished in the fire, they said. The house was in complete ruins, and their bedrooms on the second floor had collapsed into the basement along with the rest of the house. There was no way that anyone could have survived such a devastating fire.

Death certificates for the five children were issued on December 30, 1945, and a funeral was held three days later. George and Jennie were so grief stricken that they couldn't bring themselves to attend the funeral, but the surviving children did.

After the funeral, the Sodders began to have doubts about the official findings for the house fire and the fate of their children. They wanted an in-depth investigation to thoroughly explain how, among other things, faulty wiring could have caused the fire when the lights they turned on as they were trying to leave the house were working perfectly during the fire. Also, why wasn’t the phone working when it worked just a half hour before the fire started? Jennie was still convinced that the sound she heard on the roof that night had something to do with the fire.

When we think of arson, we have to think of a motive. It turned out that over the previous few years, George had been threatened on more than one occasion. The Sodders now began to wonder if their children had been kidnapped, and if the fire was a cover-up. After all, no one actually saw the children while the house was burning. When the two older boys ran out of their dark, smoke-filled bedroom, they called out to their younger brothers to get out of the room, but they never actually saw them. The three girls were supposedly asleep in the room together at the top of the stairs. There wasn’t a door at the top of the staircase, so they should have had no problem hearing the family shouting for everyone to get out of the house. And thinking back, there were no screams coming from the house as it burned, nor was there the smell of burning flesh.

Evidence began to surface that supported the couple’s suspicions. The ladder that George always kept against the house that had gone missing the night of the fire was found at the bottom of an embankment 75 feet away from the house. Who had thrown it there, and why?

The Sodders thought back to the night of the fire, and how the telephone hadn’t worked when they tried calling the fire department. It had worked perfectly just an hour before the fire when Jennie received the wrong number call. The fire chief had told them that the phone didn’t work because the wires probably burned.

At the Sodder’s request, a telephone repairman went to the scene of the fire. He told the Sodders that the house’s telephone line hadn’t been burnt in the fire, it had been cut. Even though the house was now gone, the 14-foot telephone pole that was some distance from the house hadn’t been touched by the fire. In order to cut the phone wires, someone had to have climbed the 14-foot tall pole, reached out two feet away, and cut the wires. This discovery was strange to say the least, but things were about to get much, much stranger.

The night of the fire, as the family were watching their house burn to the ground, one of the neighbors reported seeing a man stealing a block and tackle from the Sodder’s property. The man was identified, arrested, and fined. He also admitted not only to the theft--he also confessed that he had been the one who cut the phone line, thinking it was a power line. Despite these confessions, he adamantly denied having any connection to the fire. Why were the local police so quick to believe him, and why wasn’t he investigated further?

Why this man would have wanted to cut the power lines to the Sodder house just to steal a block and tackle has never been explained. It’s doubtful that anyone would risk electrocution by climbing a 14 foot pole to cut the power to the house just to steal a relatively inexpensive piece of equipment. But perhaps there was a more sinister explanation for why he cut the power to the house. Jennie said that if the power line had been cut that night, they wouldn’t have been able to turn on the lights to find their way out, and the entire family would have been killed in the fire.

Could this same man have tampered with the Sodder’s trucks the night of the fire? They had both started perfectly the day before. George believed that the trucks had been tampered with, but it’s also possible that George and John had simply flooded the engine in their haste to start the trucks.

What about the mysterious phone call that Jennie received that night? The police were actually able to locate and interview the woman who made the phone call. It turned out that she was a local woman at a party, and that the call was simply a misdialed number. At least, that’s what the police said.

The thing that the Sodders had the most trouble believing was that all traces of their children’s bodies would have completely burned in the fire. The day after the fire, the couple went back to the ruins of the house and found many household appliances in the rubble, as well as fragments of the tin roof. How could these items have survived, but not the children’s bones.

Household appliances are not human bodies. Is it possible that the fire really was hot enough to incinerate the children’s bodies, but not hot enough to destroy the appliances? Jennie did some research and found a newspaper account of a similar house fire that had killed a family of seven. In that case, the house had burned for a similar amount of time as the Sodder house, but skeletal remains of all seven of the victims were found at the scene. If this is so, then why were there absolutely no remains of the Sodder children?

Jennie began conducting experiments on burning small piles of various animal bones in a wood stove. Even after burning the bones for well over 45 minutes, they were never completely cremated. There were always large bone fragments. In some cases, full bones were found after the fire cooled.

Knowing that her experiments weren’t very scientific, Jennie consulted an employee at a local crematorium. He told her that during a cremation, pieces of human bones and teeth typically remain even after burning at 2000 degrees Fahrenheit for two hours. This is far longer and far hotter than the Sodder house fire could possibly have burned, so where were the children’s bones?

How many bones are we talking about? The human body is made up of 206 bones. The total number of bones for the five children would be 1,030. It would be virtually impossible for not one bone, or even one tooth to be found in the rubble.

What about the fire itself? Had it been set deliberately, and if so, why? After the fire, George recalled two incidents that made him believe that arson was to blame.

In October 1945, a visiting life insurance salesman became incensed after George declined his services. He was also insulted by remarks George had made against Mussolini. Like George, the man was an Italian immigrant, and he supported Mussolini. As he stormed away, he warned George, “You’ll see. Your house will go up in smoke, and your children will be destroyed.”

At first glance, this story might be dismissed as just an odd coincidence. But months after the fire, the Sodders hired a private investigator named C.C. Tinsley who discovered that this same insurance salesman was one of the jurors for the coroner’s inquest that ruled the fire an accident. What are the odds that of all the town residents that could have been considered to be on the panel, the man who threatened George and his family was chosen. And remember, the panel came to the quick conclusion that arson was not the cause of the house fire. It’s possible that this man was able to sway the jury into dismissing the fire as arson.

Earlier that same year, a man approached George looking for odd jobs around the family farm. At one point during the interview, he walked around to the back of the house and warned George that a pair of fuse boxes located there would “cause a fire someday.” George was puzzled by these remarks. The house had recently been re-wired, and the local electric company inspected the job and pronounced it safe. Unfortunately, George was unable to recall this man’s name.

The older Sodder boys recalled seeing something strange in the weeks before Christmas that year. They said that they noticed a strange car parked along the main highway, and that its occupants were watching the younger Sodder children very carefully as they walked home from school. The boys said that they never got out of the car, but they seemed overly interested in the children as they watched them walking down the road.

In the 1940s, the coal industry was under constant pressure from the mafia. George had a successful coal-trucking company in Fayetteville, and there were rumors that the mafia had tried to recruit George, but he declined. Some believed that members of the Sicilian mafia had kidnapped the five children, then started the fire in an attempt to extort money from George.

Jennie had always insisted that she was awoken by the sound of something hitting the roof just a half-hour before the fire broke out. Could the sound she heard have been some kind of incendiary device thrown at the house? In their search for answers, the Sodders located a local bus driver who had passed through Fayetteville late on the night of the fire. He said that he had seen people throwing “balls of fire” at the house.

A few months later, when the snow had melted, a small, dark green, rubber ball-like object was found in the brush near the site of the house. Upon examining it, George concluded that it was a napalm “pineapple bomb”. Someone could have coated or injected rubber balls with a flammable substance and thrown the burning balls at the house. Perhaps that is what the bus driver saw that night? And maybe that’s the sound that Jennie heard on the roof.

There are a few things to consider about Jennie’s story. First, she was awoken by the sound of something hitting the roof, then rolling off. Jennie and George slept on the first floor. Why didn’t any of the children report hearing the sound? They were on the second floor. They could have been asleep, but somehow the sound was loud enough to wake Jennie. Could the sound instead have come from John or George Jr. dropping something in their bedroom?

The bigger question, though, is that if people were indeed throwing balls of fire at the house, then why was the fire discovered in George’s first floor home office? If the fire didn’t start on the roof, then the only logical explanation is that when throwing the flaming objects at the roof didn’t work, someone came up the house, broke a window, and tossed one into George’s office.

The private investigator, C.C. Tinsley, turned up an unusual piece of evidence that seems to point to some sort of a cover-up. After 60 years, several versions of the story are floating around, but one is that fire chief Morris did find remains at the site of the fire--a human heart--but he didn’t tell the Sodders.

Tinsley and George confronted Morris about it and he admitted that he had found remains after the fire. But here’s where things get a little fuzzy. According to reports, After finding the remains, Morris took the heart, hid it in a metal dynamite box, and buried it at the scene.

When confronted, he apparently led George and the investigator to where it was buried. They dug up the box and brought the heart to a funeral director. He examined the “heart” and concluded that it was actually beef liver, and that it was untouched by the fire.

Later, the Sodders heard rumors that the fire chief had told others that he had buried the beef liver in the rubble in the hope that finding the remains would placate the family and stop the investigation.

It’s hard to know what to make of this story. The Sodders didn’t call for a more thorough investigation until long after George covered the site with soil. So, if Morris wanted to stop the Sodder’s investigation, he wouldn’t have been able to put the “heart” in the ashes.

But even if Morris had put the liver at the site earlier, why did he immediately take it away and bury it in a box where no one would find it? If he changed his mind about the cover-up, why didn’t he just throw the liver into the woods, or take it with him and dispose of it somewhere else? If he admitted to George and the investigator that he buried the liver at the site, and that he did it to stop an investigation of the fire, then why didn’t the state or local police investigate the incident? Once again we are left with many questions and few answers.

In August 1949, George persuaded Oscar Hunter, a pathologist from Washington D.C., to supervise a new search at the site of the Sodder house. A team of investigators excavated through the five feet dirt that George had put on the site, and they sifted through the dirt and ashes. The search was very thorough, and several artifacts were uncovered. These included a dictionary that had belonged to the children, some coins, and several small bone fragments. It was determined that the bones were human vertebrae. Could this be the evidence that everyone had been waiting for?

The bone fragments were sent to the Smithsonian Institute where they were examined by a specialist named Marshall T. Newman. He confirmed that the bones were from a human lumbar vertebrae. He further concluded that all of the bones were from the same individual. In his report, Newman wrote “Since the transverse recesses are fused, the age of this individual at death should have been 16 or 17 years. The top limit of age would be about 22, since the centra, which normally fuse at 23, were found to be unfused.”

Newman said that given the fact that the oldest of the missing children was only 14-years-old at the time, the bones couldn’t be from any of the five missing children. He also added that the bones showed no sign of exposure to flame. He went on to say that he agreed that it was “very strange” that those should be the only bones found at the site. In his opinion, a wood fire that had burned for such a short time should have left full skeletons behind, if not flesh.

The report concluded that the vertebrae had probably been in the soil that George Sodder had used to cover the site. How the bones ended up in the soil is another mystery. The bone fragments were returned to the Sodders in September 1949.

Sightings of the Missing Children

But what about the missing children? After the fire, witnesses began to come forward. One woman who had been watching the fire from the road said that she had seen a few of the kids looking out of a car that drove by while the house was still burning. Not knowing who this witness is, we have no way of knowing if she actually knew the children, and if she would have recognized their faces. In addition, anyone would slow down to look at a house on fire, and if there were children in the car, they too would have peered out the window to see what was going on. Still, one has to ask, what family would be driving around at 2 or 3 AM with children in the car?

A woman who worked at a rest stop between Fayetteville and Charleston also contacted the Sodders. She said that she’d served the children breakfast the next morning, and that she noticed a car with Florida license plates in the parking lot while they were there.

If the rest stop was about half-way between Fayetteville and Charleston, the drive would have taken roughly a half hour. If the children left the house before Jennie answered the phone, it would have been sometime between 11 PM and midnight. If someone kidnapped the kids and ushered them out of the house, it’s possible that they had first taken them to a local house. Perhaps they had a change of clothes for the kids, all of whom would have left the house in their pajamas. After ordering them to change, they could have put them in the car and made their way towards Charleston, stopping along the way at the rest stop.

But I find this scenario highly unlikely. Kidnappers would never have taken the five children out in public. If anything, they would have kept them completely hidden. Remember, the two oldest missing children were 14 and 12. Children that age might attempt to get someone’s attention. Bringing five children into a busy rest stop to have what must have been a long breakfast would be the last thing a kidnapper would do.

In 1952, the Sodders put up a billboard at the site of the house, and another along US Route 60 near Ansted, West Virginia. The billboard showed pictures of the missing children along with the caption: “What was their fate? Kidnapped--Murdered--Or are they still alive? $5000 Reward”. The reward was later raised to $10,000.

After the billboard went up, tips began to trickle in. A St. Louis woman contacted the family saying that Martha, the oldest missing girl, was in a convent there. A patron in a bar in Texas gave the tip that she had overheard an incriminating conversation about a Christmas Eve fire in West Virginia. Someone in Florida claimed the children were staying with a distant relative of Jennie’s. In that case, the relatives were investigated and had to prove that the children were actually their own. George traveled the country to investigate every lead, but he always came home empty handed.

A woman named Ida Crutchfield who ran a hotel in Charleston saw the billboard and contacted the Sodders. She claimed that she had seen the children about a week after the fire. She said that they came into the hotel sometime after midnight accompanied by two men and two women. She described the adults as appearing to be “of Italian extraction.” When she attempted to speak with the children, one of the men gave her a hostile look and began talking rapidly in Italian, silencing the whole group. She also said that they left early the next morning.

What’s interesting about this story is the woman specified that the individuals seemed to be Italian. She had no way of knowing the Sodder’s Italian heritage, or the incident where the Italian salesman threatened George for insulting Mussalini. But as with every other tip, this one was a dead end.

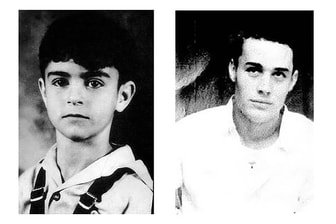

The most credible and mysterious information the Sodders ever received came years later. In 1967, a letter came in the mail addressed to Jennie. It was postmarked from Central City, Kentucky. It had no return address. Inside the envelope was a photo of a young man, around 30-years-old. His features strongly resembled those of Louis Sodder, who would have been around that age at the time. On the back was the following text:

Louis Sodder

I love brother Frankie

IilI boys

A90132 or 3

The meaning of the writing on the back of the mysterious photo has never been deciphered. Recently, the granddaughter of one of the surviving Sodder children said that her mother always told her that the writing said “Aged 32 or 3” not “A90132 or 3”. She said that the writing was in script, and that the 9 was actually a letter ‘g’ and the ‘0’ was the ‘e’, and the ‘1’ was the ‘d’. The message “I love brother Frankie” remains a mystery.

The Sodders hired a private detective to investigate the strange photo, but he never reported back to them and they were unable to locate him afterwards. In reading the account of this lead, and of the missing private detective, I wonder why they didn’t pursue the lead further with another detective. The family were so convinced that the photo was genuine that they added it to the billboard, and they displayed a copy of the photo in their home.

The Sodder’s never stopped searching for their lost children. Geroge even went so far as to contact the FBI for help in investigating what he considered to be a kidnapping. Then director J. Edgar Hoover personally responded to George’s letters. He wrote, "Although I would like to be of service, the matter related appears to be of local character and does not come within the investigative jurisdiction of this bureau." He added that if the local authorities requested the bureau's assistance, he would of course direct agents to assist, but the Fayetteville police and fire departments declined to do so. Was there a reason why they refused to cooperate with the FBI? We’ll never know.

George died in 1969, but Jennie, George Jr., Joe, Marion, and Sylvia continued the search for the missing kids. John never talked about the fire, and thought that his family should just move on with their lives.

Jennie continued to live in the family home, wearing black in mourning and tending the memorial garden at the site of the fire until her death in1989. After Jennie’s death, the family finally took down the weathered billboards that had stood for 37 years.

As the years went on, the surviving children passed away. Today 77-year-old Syliva Sodder is the only one left. To this day she remains convinced that her siblings did not die in the fire.

With no trace of human remains found at the scene, as painful as it would be for the family to accept, is it possible that the five Sodder children actually did die in the fire?

After the fire, the family members were interviewed by the State Police. John first told them that when the family was fleeing the house, he went in and shook his brothers and sisters to wake them up before running out of the room. He later changed his story and said that he just called out to them, then left the room thinking they heard him.

The family said that John told them that he told the police that he tried to shake them because he felt that’s what he should have done. They said that he felt guilty about NOT shaking them awake, and that he just called to them. This could be true, but it could also be true that he did exactly what he first said he did.

If John did shake them awake, there are a few extremely important things to consider. First, it means that he was the last to see the children alive. Second, it means that the five children actually did die in the fire. And third, it means that for over 50 years, John had been lying--not only to his family, but to the world.

But would he really continue to lie all of those years just to cover up his guilt at not having tried harder to wake his siblings up? He never wanted to talk about the fire, but would he actually watch his family search for his missing brothers and sisters for over fifty years when he knew that they were dead? We’ll never know. If there was a confession to make, John took it to his grave.

Modern day fire professionals believe that the five children probably died of smoke inhalation, and that they were either dead or unconscious when the rest of the family were roused. It’s not uncommon for some people to die of smoke inhalation who are right next to other people who survive. This could explain why John and George Jr. survived the fire, but their younger brothers and sisters might not have.

What about the fact that no one reported the smell of burning flesh during the fire? From all reports, it was a very windy night. As a result, no one would have been able to stand downwind from the fire. Smoke and sparks would have been flying in the direction of the wind, so it’s not surprising that no one smelled anything unusual.

What about the lack of human remains in the ashes? The cremation specialist told the Sodders that bones remain even after burning for two hours in 2000 temperatures. The Sodder house was only on fire for 45 minutes. Why weren’t there any remains if the fire burned for such a short time? In reality, the home was probably burning for much longer than 45 minutes. Although there were active flames for 45 minutes, the fire would have continued to burn underneath the debris and ashes. The fire department showed up 5 ½ hours after the fire started. They put water on the site to cool it down so they could sift through the ashes, but the fire itself was smoldering up until that point.

With the bodies burning in fire for that long, very little would have remained. And it’s important to remember that the fire department sifted through the ashes for a very short time. It may not be that there weren’t any remains, they just might have missed them.

What about the investigation that was done in 1949? Those were professional investigators, and they didn’t find any of the children’s bones either. Keep in mind that four years prior to the investigation, George had piled up to 5 feet of soil onto the site against the wishes of the fire chief. Although the investigation was considered to have been very thorough by 1949 standards, by today’s standards it was far from it. Today, an excavation and investigation by a large team of researchers would take months to complete, not just a few days.

In spite of evidence to support the theory that the children died in the fire, there is equal evidence supporting the theory that they were kidnapped, possibly by the Sicilian mafia. And some modern day fire experts and cremation workers insist that not only should there have been some bones after the fire, there should have been a lot of bones and teeth left over, even if the fire had burned all night as some have suggested. As a result, the Sodder Children disappearance continues to be one of the most baffling and talked about unsolved mysteries of all time.

George Sodder died in 1969. If anyone thinks that he didn’t actually believe that his children were still alive, they need to take a look at his tombstone. On it is carved, “In Memory of George Sodder who believed in justice for everyone, but was denied justice by the law when his five children were kidnapped Christmas Eve 1945 at Fayetteville, W. VA.”

Resources

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-children-who-went-up-in-smoke-172429802/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sodder_children_disappearance

https://thetruecrimefiles.com/sodder-children-disappearance/

https://mywvhome.com/forties/sodder.html

https://museumofwitchcraftandmagic.co.uk/object/animal-liver/

https://sorcerer.blog/2017/05/22/the-age-of-black-magic-step-ten/

https://medium.com/the-true-crime-times/the-sodder-family-a-christmas-inferno-f39f60843412

http://sites.rootsweb.com/~wvrcbiog/WhatReallyHappenedToChildrena.html

https://defrostingcoldcases.com/case-month-sodder-children/

reddit.com/r/UnresolvedMysteries/comments/cpvxde/the_sodder_children_new_leads/

http://truecrimediscussions.blogspot.com/2015/08/the-missing-sodder-children.html

https://sites.psu.edu/resorensenpassion/

https://www.websleuths.com/forums/threads/the-sodder-family-this-is-important-medical-condition-causes-spine-fusing-early.326967/

https://www.timeswv.com/news/their-fate-kidnapped-murdered-or-are-they-still-alive/article_be5920fe-a3f1-11e6-a3fc-43908d62effb.html

https://scarestreet.com/sodder-children/

https://www.websleuths.com/forums/threads/wv-sodder-family-5-children-christmas-eve-1945-2.35000/page-3

https://stacyhorn.com/2005/12/28/long-long-long-sodder-post/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed