Mass hysteria is a phenomenon that spreads the illusion of a threat, whether real or imaginary, throughout a population. This is usually the result of rumor, or of fear. When mass hysteria hits, the behavior that people exhibit is often totally bizarre. Need an example? I’ve got plenty!

During the Middle Ages, a nun living in a French convent began to meow like a cat. No one knew why, but soon, some of the other nuns in the convent also started meowing. Soon, ALL the nuns were meowing away just like a litter of kittens. They would meow together, kind of like a cat choir, for a certain period of time every day. The community was puzzled, and probably more than a little amused and entertained by it all. I know if I lived in that town, I’d be hanging outside the convent everyday waiting for the kitty concert to start. What put a stop to this strange behavior? The police. They stepped in and threatened to whip the nuns if they didn’t shut the hell up -- so they did.

Not to pick on nuns here, but there was another case of mass hysteria that involved nuns. In the 15th Century, a nun in a German convent began biting her companions. Like the beginning of all mass hysteria cases, her actions were totally inexplicable. Strangely enough though, other nuns began biting each other at other convents. Nuns started biting each other across Germany, then the behavior spread to Holland. As far away as Italy, nuns were biting each other for no reason at all.

One of the most famous cases of mass hysteria occurred in July of 1518 in the French city of Strasbourg. This case didn’t involve meowing or biting. It started out quite innocently. One day, a woman named Mrs. Trofea, began dancing feverishly in the street. Her dance lasted about six days. Within a week, 34 others had joined in the dance, and within a month there were approximately 400 predominately female dancers. But the dancing wasn’t without its consequences. It was reported that at one point, as many as 15 people per day died from the result of the dancing. Some died of exhaustion. Others had heart attacks and strokes. The authorities were called in. Something had to be done, but what? “I know,” they said. “We’ll encourage more dancing so they’ll get it out of their system!” So they built a special stage for the dancers, opened two dance halls, and made a market available as a place where people could dance day and night. To help increase the effectiveness of the cure, the authorities even paid musicians to keep the dancers moving. The idea was a colossal failure. The number of dancers underwent a dramatic increase. In the end, the dancing lasted about two months, and then ended as mysteriously as it had begun.

Jumping ahead to the 20th century we find the strange case of the laughter epidemic of 1962. Three girls at a boarding school in Tanzania started laughing, and they couldn’t stop. The laughter spread to 95 of the 159 students, all of whom were girls between the ages of 12 and 18. These laughing seizures lasted from as little as a few hours, to as long as 16 days. Two months later, the school was forced to shut down. But this only made the laughing epidemic worse. After the girls were sent home, the laughing spread to their villages. The school reopened after a few months, but then had to close again as more and more girls found themselves laughing uncontrollably. Soon, another school found itself in the same predicament where 48 girls were affected. A few weeks later, two boys schools had to be closed when the boys ‘caught’ the laughing hysteria.

The list of examples of mass hysteria goes on and on. It includes hundreds of people fainting; people having convulsions; scores of men, women and children having seizures; people claiming to have been attacked by a mysterious man with a mallet and bright buckles on his shoes; and of course, the great ‘Clown Panic of 2016’ where clown sightings were reported across the country.

But of course, the most famous example of mass hysteria of all were the Salem Witch trials of 1693. In the end, between 140 and 150 people were arrested for witchcraft. Of these, 19 were hanged, and one died of torture. In addition, four people died in prison awaiting trial, and two dogs were put to death. The others who were arrested were either found guilty but pardoned, never indicted, found not guilty, or escaped from jail.

Like the Salem Witch Trials, the New England Vampire panic was set off by one of our most primal emotions -- Fear. Fear is a reaction to anything that threatens our safety or security. It alerts us to the possibility that our physical selves may be harmed which then motivates us to protect ourselves. When looked at in this way, fear is a good thing. But fear can get out of hand, and when it spreads across a population … well, things can get ugly.

A full century after the Salem Witch Trials, citizens of Rhode Island began hearing whispers of something even darker than witchcraft. People began to suspect that there were vampires in their midst. You heard it right - Vampires! But what is even more disturbing, they didn’t think the vampires were strangers. Many people believed that members of their own families were vampires; and like Van Helsing, they hunted them down and made sure that they wouldn’t drink even one more drop of blood.

I’ll begin our search for Vampires in New England in 1784. In June of that year, The Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer posted a letter to the editor from a Willington, Connecticut town councilman. In it, he cautioned readers against being influenced by a ‘quack doctor’ who was encouraging families to dig up and burn their relatives bodies. The letter went on to say that several children’s bodies were exhumed at this doctor’s request, and that the families thought that the burning of the bodies would stop consumption, now known as tuberculosis, from spreading throughout the family. Although the word vampire wasn’t used in describing the supposed cause of the disease, it’s obvious that people believed that a relative who died of consumption somehow came back to life and returned to spread the disease throughout the family. So, naturally, exhuming their body and burning it seemed to be the best way to keep them from coming back.

Where did this gruesome practice of exhuming bodies start? It’s important to remember that many immigrants in America’s early history came from Europe, and they brought their traditions, folklore, and superstitions with them. Throughout Europe, exhumation of bodies of those thought to be vampires was not uncommon, but what was done to the bodies afterward varied by region. Some corpses were beheaded, while others had their feet bound with thorns. Even if a body was badly decomposed, it was often beheaded and the rest of the bones carefully rearranged to prevent the vampire from rising. As we will see, this practice of rearranging the bones of the dead made its way to New England.

In 1790, the first case of New England vampirism as such was that of Rachel Harris Burton from Manchester, Vermont. Less than a year after marrying Captain Isaac Burton, the deacon in the town’s Congregational Church, Rachel died of tuberculosis. A year later, the Captain married Rachel’s stepsister, Hulda, and soon after she to began exhibiting symptoms similar to Rachel’s. Because rumors of vampirism had begun to spread across New England, family and friends soon began to suspect that Rachel was responsible; that she had risen from the grave as a vampire and was making Hulda sick by sucking her blood. So on a frigid day in February of 1793, three years after Rachel’s death, between 500 and 1000 Manchester residents gathered together to watch as the liver, heart and lungs were removed from Rachel’s exhumed, rotting corpse, placed on a blacksmith’s forge, and set on fire. There is some speculation that pieces of the organs were saved to make a medicine to help cure Hulga; but whether this is true or not, we’ll never know. What we do know is that Hulga died seven months later. Because the ‘cure’ didn’t work, the townspeople began suspect that Rachel hadn’t been a vampire after all. Their conclusion? Witchcraft must have been responsible. Case closed.

Another tragic example of exhumation and vampirism was that of the Spalding Family in Dummerston, Vermont. In the 1790s, Lieutenant Leonard Spaulding was grieving the loss of six of his eleven adult children from tuberculosis. Soon, another of his children became ill. Desperate to stop the spread of the disease, the Lieutenant ordered that the most recently deceased child be dug up, and the vital organs removed and burned. It is not recorded if the child who was ill survived. But it is important to take note that when Spalding’s son Reuben was buried in 1794, his grave was set apart from those of his other family members. Why? There was a vampire related belief that vines would grow between buried caskets, and that once all of the burials in a plot had been connected by these vines, another family member would die. By burying Ruben away from the rest of his family, Spalding hoped that this would break the vampire-vine-chain, and that other family members would be spared.

Some of the most interesting cases of New England vampirism involve those where people claim to have been visited by deceased family members or by other mysterious figures prior to their falling ill. One such case is that of Abigail Staples of Cumberland, Rhode Island. A short time after twenty-three year old Abigail’s death from tuberculosis, her sister Lavinia began to show symptoms of the disease. She also began telling the family of dreams she was having in which a shadowy figure was sitting heavily on her chest, sucking the breath out of her -- and during the dreams, her family heard her calling out Abigail’s name. So, in February 1796, Stephen Staples was given permission by the Cumberland town council to exhume Abigail’s body. Although the town officials gave their consent for the exhumation, they said that they considered it ‘an experiment’ to save Lavinia’s life, and noted that the decision was made ‘against the better conscience of this council’. Unfortunately, there is no record of what came of the exhumation; nor is there a record of what became of Lavinia.

One of the most famous cases of the New England vampire panic occurred in 1799, and it centered around a girl named Sarah Tillinghast. Sarah lived with her family in Exeter, Rhode Island. She was said to be a very sensitive girl who often spent time reading poetry and wandering the small, rural graveyards where Revolutionary soldiers were buried.

One night, Sarah’s father, Stuckley Tillinghast, had a disturbing dream. In the dream, half of his orchard died. Stuckley was an apple farmer, and he feared that the dream was an omen that he might lose his livelihood. He and his wife had 8 daughters and 6 sons to support, so it is no wonder that he found the dream so disturbing. Sometime after Stuckley had this dream, Sarah came home one day and said that she wasn’t feeling well. She took to bed, and within a few weeks developed a high fever. A few weeks later, she died of tuberculosis. But of course, the story doesn’t end here. The family was still grieving when Sarah’s brother, James, came down to breakfast looking pale and shivering. He complained that he felt as if there was a weight on his chest, and then said something chilling. He said that Sarah had come to him and sat on his bed in the middle of the night. The family dismissed it as James imagination brought on by grieving for his sister. Within a few weeks, James too had passed away.

But Sarah and James were just the beginning of the family tragedy. Shortly after James’ death, two more Tillinghast children died. Both had claimed that Sarah had visited them in the night. These days, stories of visitations from deceased family members are taken as a comforting sign; that although a loved one has passed, they are doing just fine on the other side. But in the late 18th century, things were different. Religious belief mixed with folklore and superstition were the recipe for the acceptance in things that today might not make much sense. Things such as fairies, gnomes, trolls, woodland spirits, and Vampires. To the Tillinghast family, Sarah’s nocturnal visits to her brothers and sisters meant just one thing. That she was returning from the grave to draw life from the remaining family members - that Sarah was a vampire.

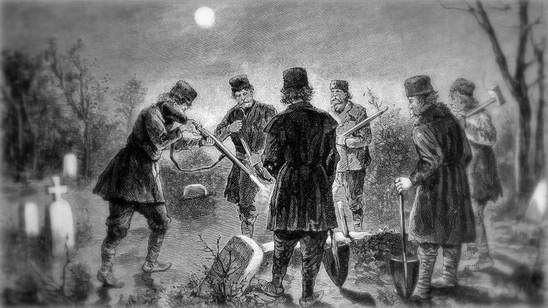

Soon, more Tillinghast children died. Then, Honour Tillinghast, mother of all of the deceased children, became ill. As she lay on her death bed, she claimed that all of her dead children were calling to her. For Stuckley Tillinghast, this was the last straw. Early one morning he and his farmhand Caleb went out to the cemetery where Sarah was buried. They took with them a long hunting knife, a bottle of lamp oil, and two shovels. As the sun was rising, the two men dug up Sarah’s casket and turned back the creaking lid. Even though she had been dead over 18 months, she looked as if she was just asleep. There was no sign of decomposition. Seeing his daughter’s face looking flushed as if with blood, Stuckley Tillinghast took his hunting knife and thrust it deep into his daughter’s chest. Digging through flesh, muscle and bone, he cut out her heart. Later, Stuckley claimed that her body gushed with blood. He took her heart and lay it on a nearby stone. There he doused it with lamp oil and set it on fire. He and Caleb watched as the heart was reduced to ashes, then the two of them reburied Sarah. Their job was done.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, Honour Tillinghast recovered from her illness. In the end, Stuckley Tillinghast’s dream had come true in a symbolic sense. Half of his ‘orchard’ -- seven of his fourteen children -- had died. But after burning Sarah’s heart, no more children died, and there were no further reports of Sarah appearing to the family. To the Tillighasts, the vampire curse had finally ended thanks to Stuckley’s intervention. And because the entire town knew how he had prevented his family from further deaths, the belief in Vampires was strengthened and word spread near and far.

The Last American Vampire: Mercy Brown

George Brown must have felt as if his family was cursed. Tuberculosis had claimed the life of his wife Mary Brown in 1883; then six months later, his 20-year old daughter Mary Olive succumbed to the same disease. It seemed as if the epidemic had finally run its course, but in 1890 George’s only son, Edwin, contracted tuberculosis as well. George watched helplessly as his son struggled to breath, and constantly coughed up blood. Edwin was sent to Colorado, hoping the different climate would help cure him, but he returned to Rhode Island two years later showing no signs of improvement. While Edwin grew weaker and weaker in the winter of 1892, 19-year-old Mercy Lena Brown passed away after a year of illness.

George Brown was at his wits end. He had to do something to save his son, the only remaining member of his family, Edwin. Since medical science failed to help Edwin, residents of Exeter began to talk about vampires as being the real culprit. They reasoned - find and destroy the vampire who was responsible for spreading the disease, and the disease will be stopped dead in its tracks. A group of Exeter residents believed that Edwin’s mother, Mary Brown, or one of his sisters may be one of the undead, a vampire, and sucking the life out of poor Edwin from beyond the grave.

So it was that on March 17, 1892, George Brown reluctantly agreed to allow his relatives and neighbors exhume the bodies of his loved ones interred at the Chestnut Hill Cemetery in an effort to stop the disease. George said that he did not believe in vampires, but he was willing to try anything.

A small crowd gathered in the graveyard behind the town’s Baptist Church. There, a group of people exhumed the bodies of Mary Brown and Mary Olive Brown. They opened their caskets, but the only thing they found inside were bones. Next, they turned their attention to the casket of Mercy Brown who been buried just eight weeks earlier. When the lid was lifted off of her coffin, the townspeople gasped in horror. Mercy was lying on her side, and her face was flushed as if she was still alive. Someone quickly took a long knife and thrust it into Mercy’s chest, removing her heart and lungs. Mysteriously, there was still blood in her heart, and in her veins.

While he was unable to explain why Mercy was lying on her side in her coffin, Dr. Harold Metcalf, who had raised objections about the exhumations from the very start, said that the preserved state of the body was simply due to the short amount of time Mercy had been dead, and that the cold weather had preserved her body. But the people of Exeter ignored the doctor’s explanations. They built a fire on a pile of rocks in the churchyard, then took Mercy’s heart and lungs and cremated them. They returned to Edwin’s house with the ashes of his dead sister’s heart, mixed them with water, and fed them to him. Disgusting? Yes! But it was thought that this was the only way to prevent Edwin from dying. Sadly, and not unsurprisingly, Edwin died two months later.

Looking at the timeline of events, it’s baffling how anyone would have suspected that Mercy was responsible for her family’s illness - vampire or no vampire. Her mother and sister had died nearly 10 years earlier, and her brother had become ill two years before she died. But, as we’ve seen, cases of mass hysteria grow out of fear and superstition, and very few people often stop to think whether or not any of it makes sense.

In 1990, children playing near a hillside gravel mine in Griswold, Connecticut found something that they thought was really cool. A skull that was in a grave with other bones. One of the boys ran home and showed his parents. The police were called, and the area was secured. At first it was thought that the skull may belong to a victim of a local serial killer, Michael Ross. But it soon became clear that the bones were more than a century old. Archaeologists were called in to excavate the site, and they discovered that the bones were part of a family burial plot from the colonial-era. New England is full of such unmarked family graveyards, so the 29 burial plots were pretty typical of the time. That is, all except one plot - burial number four.

Burial number four was only one of two stone crypts in the cemetery, and it lay several feet below the surface. When the first of the two large, flat stones was removed from the crypt, the archaeologists saw the remains of a red painted coffin, and a pair of skeletal feet. But when they removed the second stone, they saw that bones of the rest of this individual had been completely rearranged, and that the skeleton had been beheaded. The skull and thigh bones rested on the ribs and vertebrae. Further investigation showed that the beheading and other injuries to the rib bones occurred roughly five years after death. And, someone had smashed the coffin. The person buried in the plot number four, a man in his 50s who was buried sometime in the 1830s, was almost certainly accused of being a vampire. The fractured ribs point to just one conclusion - his heart had been removed 5 years after his death.

The New England Vampire panic finally died off in the late 1800s once science had discovered the cause of tuberculosis. But it illustrates to what lengths people will go to save themselves and their families. The exhumation of bodies and the burning of hearts and other vital organs were often clandestine, lantern-lit affairs. But some were quite public and even had an air of festivity. In 1830, one vampire heart was set on fire in the Woodstock Vermont town green; and in Manchester up to a thousand people turned up to witness the burning of Rachel Burton Harris’ heart, liver and lungs.

While vampires don’t really exist, it’s only a matter of time before a new mass hysteria panic rears its ugly head. And afterward, historians will shake their heads and say, “What on earth were those people thinking?”

Resources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vampire

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-new-england-vampire-panic-36482878/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_England_vampire_panic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_mass_hysteria_cases#cite_note-Bartholomew_2001-2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dancing_plague_of_1518

https://www.vampires.com/a-true-rhode-island-vampire/

http://realparanormalexperiences.com/rhode-island-vampires-sarah-tillinghast

http://elemaredesign.com/hauntedri3/sites.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_EzFykZfn0M

https://locationsoflore.com/2018/07/26/the-vampire-case-of-sarah-tillinghast/

http://www.thewesterlysun.com/news/state/2598348-129/documentary-traces-ri-roots-of-the-vampire-motif.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed